There is a distinct smell in old-school engineering wings. It’s a mix of cutting fluid, oxidized metal, and gasoline. It’s the smell of the last century.

If you walk into the prototyping floor of a company like Lucid or Rivian today, that smell is gone. It’s been replaced by the hum of cooling fans and the click of high-voltage relays. The industry has completely reinvented itself in the last five years, but academia is still struggling to turn the ship.

We are currently graduating thousands of engineers who are experts in technologies that are fading away. They can calculate the efficiency of a diesel cycle in their sleep, but they freeze up when looking at a battery pack architecture. This isn’t a curriculum issue; it’s a hardware issue. You can’t teach the future of transportation with a whiteboard and a projector. For an institute to stay viable, building a dedicated electric vehicle lab is the only way to bridge the gap between the classroom and the assembly line.

The End of the “Gearhead” Era

For a long time, mechanical engineers stayed in their lane, and electrical engineers stayed in theirs. They rarely spoke to each other. An electric vehicle (EV) destroys that arrangement.

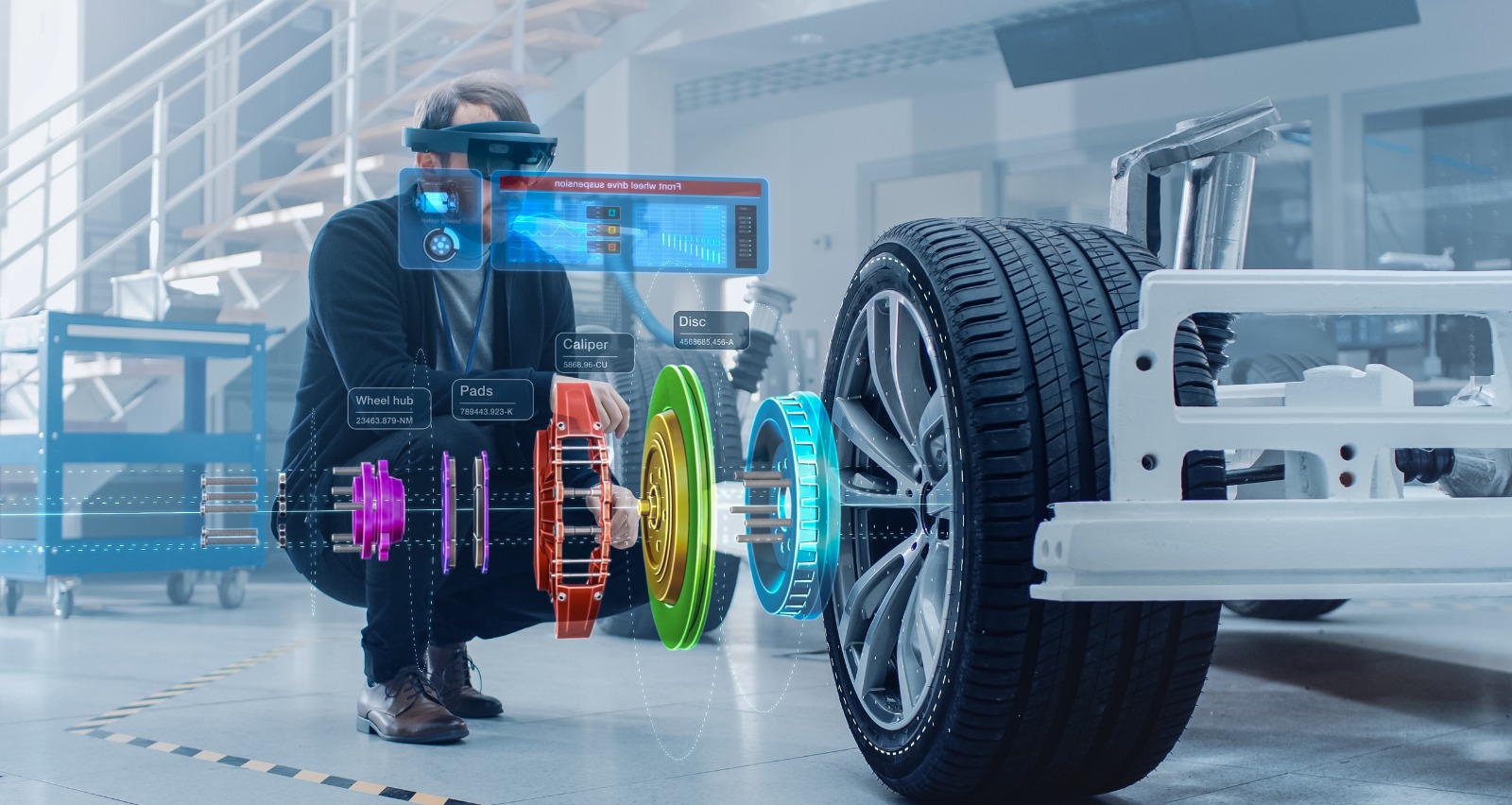

An EV is a messy collision of chemistry, software, mechanics, and high-voltage physics. You can’t fix a thermal issue in a battery pack without understanding fluid dynamics, but you also can’t understand the heat generation without knowing the electrical current flow — something that students and researchers explore hands-on in an electric vehicle lab.

Students today can’t afford to be specialists in just one thing. They need to be systems engineers. A proper EV lab forces this collision. It’s the place where a code monkey learns why torque curves matter, and where a grease monkey learns that a line of bad code can melt a motor. You can’t teach that integration on a whiteboard. They have to see the systems fight each other in the real world.

Respecting the Orange Cable

Let’s be blunt about safety. You can mess up on a 12-volt car battery and get a spark. You mess up on an 800-volt EV architecture, and you don’t go home.

Universities have a moral obligation to teach high-voltage safety, and that goes beyond a PowerPoint presentation. Students need muscle memory. They need to stand in front of a powertrain test bench, wearing Class 0 gloves, and physically perform the lock-out/tag-out procedures. They need to see what happens when isolation fails.

An electric vehicle lab is a controlled environment where students can make mistakes without lethal consequences. By the time they graduate and hit the factory floor, respecting that bright orange high-voltage cable should be instinct, not just a rule they read in a handbook.

Chasing the Sun: The Infrastructure Problem

We tend to focus on the car, but the car is just a battery on wheels. The bigger engineering challenge is the grid. How do we charge millions of these things without blowing up the transformers?

This is where the curriculum gets tricky. We are moving toward a world where your car might power your house (V2H) or stabilize the grid (V2G). To teach this, you need to simulate the entire energy loop—from the sun to the wheel.

But here is the problem: you can’t rely on the actual weather for lab exams. You can’t tell a class, “Sorry, we can’t test the solar charging efficiency today because it’s raining.” That’s why an electric vehicle lab with simulators and controlled setups is essential for students to safely and reliably experiment with the full energy system.

To get around this, labs are bringing the sun indoors. They use a piece of hardware called a pv emulator. Think of it as a programmable power supply that mimics the exact behavior of a solar panel array. You can dial in the settings to simulate a passing cloud, a sunset, or a perfect summer noon. With a pv emulator, students can stress-test how an EV charger responds to fluctuating renewable energy in real-time. It removes the variables you can’t control so you can focus on the engineering you can control.

The Employability Crisis

Talk to any recruiter at Tesla, Rivian, or Tata Motors. They all say the same thing: “We have to retrain everyone we hire.”

Graduates are coming out with strong theory but zero context. They know Ohm’s law, but they’ve never seen a battery management system balance cells in real-time. They understand magnetism, but they haven’t seen an inverter induce noise into a sensor — something students can experience firsthand in an electric vehicle lab, gaining the practical context that bridges classroom theory with real-world EV challenges.

Institutes that invest in ev labs are effectively cutting the training time for future employers. When a student can put on their resume that they’ve run drive cycles on a dynamometer or tested MPPT algorithms on a solar-connected charger, they jump to the front of the line.

The Verdict

The industry isn’t waiting for academia to catch up. The transition to electric is messy, expensive, and fast.

Engineering institutes have a choice. They can keep teaching the history of transportation, or they can start building the future of it. Setting up an EV lab—complete with battery cyclers, motor test rigs, and grid simulation tools—is a heavy investment. But the alternative is handing out degrees that are rapidly losing their value. The road ahead is electric; the classroom needs to be too.